Weekly insight

Published

25 Jan 2021

Regular insights from the A63 Castle Street archaeology team

Share this article

Friday 08 October 2021 – Building detailed, 3D models of archaeological sites using Photogrammetry

Photogrammetry is a tool used by archaeologists to create scaled 3D models of features and areas of sites. To do this, once an area has been excavated surveyors will mark out control points within the site and the area is then photographed using a drone or a polecam extended a few meters up to give us a bird’s eye view of the whole feature. The images are taken overlapping one another at various positions and angles so that every side of the feature is photographed. As you can imagine, this results in a lot of images being taken!

Think about taking photos of a cake. Each photo taken must overlap with one of the previous photos until every angle of the cake has been photographed. These photos are then stitched together in a 3D space to create an exact image of the original cake. We can then manipulate the image to view every aspect of the cake.

A GPS is then used to scan in where the control points are. The GPS connects to satellites to assign the OS coordinates to each control point to pinpoint exactly where in the world each specific point is using OS maps.

A control point used by the GPS to assign coordinates to

Once this is done, we are able to combine all of the images produced as well as the survey coordinate information into a single 3D model through the use of specialist software. By creating these models, we can examine sites and features at the appropriate scales and at various angles in incredible detail for future reference. This process also helps to supplement our other post-excavation recording methods such as plan drawings.

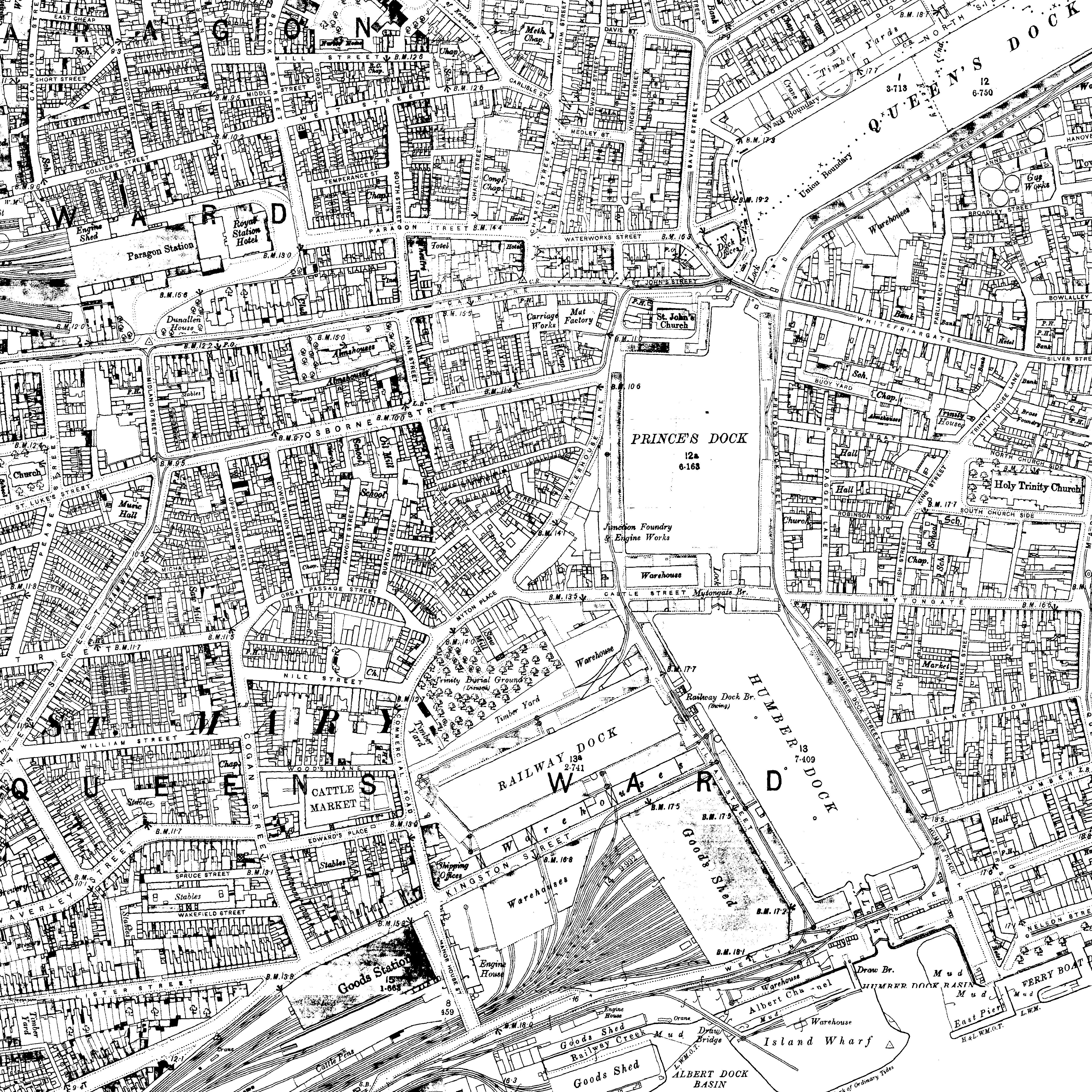

Since the tents have come down, the focus of our activity at Trinity Burial Ground has been in the north-east corner of the site. We know from historical records that this was the site of a jail – or gaol – in the late 18th century. It opened in 1785 and closed in 1829 when a new, larger, gaol was built on Kingston Street. By the mid-19th century, the site of the Castle Street Gaol was occupied by a timber yard with two small buildings on the street frontage. This was just one of many such yards in the area of the docks, indicating the importance of the Baltic timber trade to the town’s economy. By the 1860s the site was again redeveloped, apparently as a sawmill, with buildings arranged around a central courtyard. The sawmill was replaced in the late 19th century, the eastern part becoming the site of a Brass and Copper works, the western part being occupied by a lead works.

Our archaeologists have been investigating the site in two halves, to fit in with wider groundworks. The southern part was completed in July, and we are now starting on the northern half. We are excavating and recording layers of overlapping structures and demolition rubble, comparing them to the plans we have of the buildings which once stood here. The uppermost structures excavated by our team are the most recent, and we’ve found evidence of earlier buildings as we’ve dug deeper.

We’ve been taking overlapping aerial photographs of the area to accurately measure and record the details of these structures and have used these to create a 3D model. You can take a virtual tour around the excavation area on our Sketchfab account.

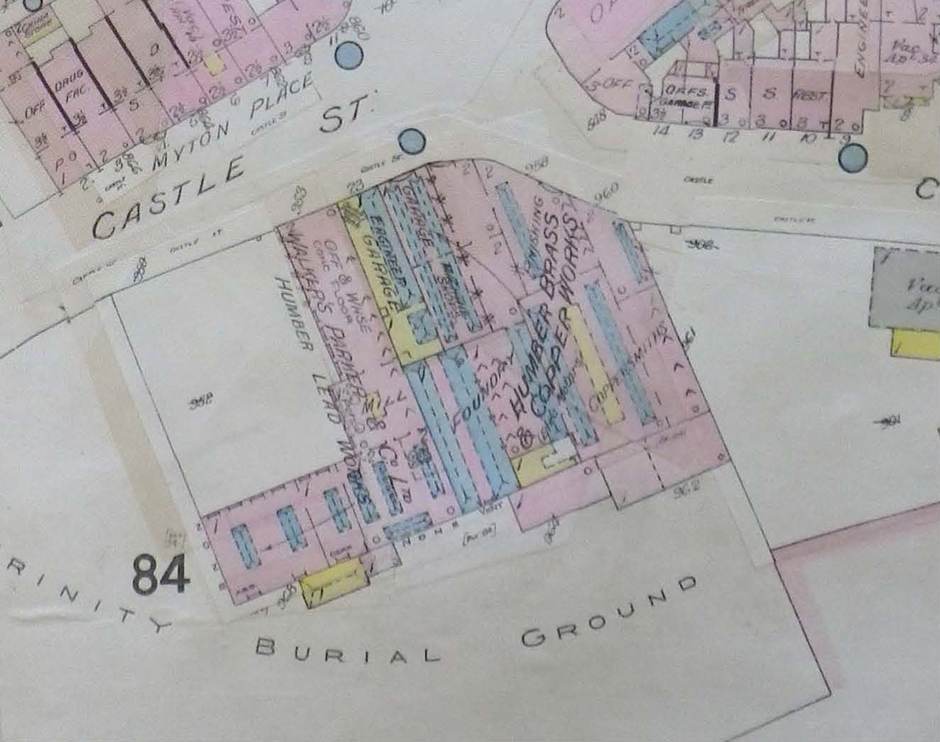

Fortunately, a plan from 1906 (produced to assess the fire risk of the building) shows the layout of the lead and brass foundries in some detail. Humber Brass and Copper Works was founded in 1884 and occupied the eastern half of the site. The brass foundry has a series of small-celled rooms with concrete floors, and a large brick-lined square pit, that may originally have held sand for casting. It is within those structures that the molten brass would have been poured into moulds to cast objects. The site of a separate coppersmith’s workshop, probably for more delicate work, also lay within the excavation area.

The lead works were owned by Walker’s, Parker’s and Co Ltd and it was built c.1900. On the ground, we’ve found a large circular structure in the western half of the site, which looks likely to be the furnace from the lead foundry. It’s made of refractory bricks designed mainly to withstand high heat and encloses a series of channels that connected to a flue. Excavation of the northern part may reveal structures and features associated with finishing the metalwork.

The Goad Insurance Map of 1906 showing the lead and brass foundries

There was very little evidence for the sawmill that occupied the site during the last quarter of the 19th century. It is possible that it was a wooden building without substantial foundations. Similarly, so far there has been little evidence of the timber yard, although a sleeper wall formed of re-used handmade bricks may have belonged to an associated and short-lived structure.

The Ordnance Survey Map of 1886 showing the saw mill

Several structures visible outside the footprint of the foundry buildings look to be the remains of the gaol, made from a thin handmade brick. Now that we’ve recorded the later buildings, we’re revealing more of the gaol remains to understand more about how it was constructed and used.

The tents have been a feature of Castle Street for almost a year and, under their protection, the remains of around 9,500 burials have been carefully and respectfully excavated by our archaeological team. Further analysis is continuing on-site before the funerary remains are reburied within the grounds of the minster, with associated personal possessions and coffin fittings. In recent weeks, a selection of bones have been x-rayed using a mobile x-radiography facility, and specialists from the Francis Crick Institute have taken DNA samples to analyse for tuberculosis and similar bacterial pathogens and explore family groups and ancestry.

As our work on Trinity Burial Ground nears completion, we have been turning our attention to the earlier 18th-century jail – or gaol as it was previously known – which stood at the north-east corner of the burial ground. The gaol was established at the same time as the burial ground for the parish of Holy Trinity outside the city boundaries by the Kingston upon Hull Improvement Act in 1783. This was a period of prison reform when the likes of John Howard and Elizabeth Fry promoted the need for better conditions, productive labour, and religious instruction.

It was referred to as the New Gaol and housed men and women awaiting trial, those incarcerated for minor offences, and debtors, as well as those due to be transported for more serious crimes. It closed in 1829 when the functions of the county gaol and the borough House of Correction were combined in one new gaol. The plot later became a sawmill in the 19th century and a brass and copper works and lead plant in the early 20th century.

So far, we’ve revealed part of the gaol’s footprint and, interestingly, part of a basement that seems to have been sub-divided into cells, possibly for holding more disobedient prisoners. A 19th-century record of the gaol doesn’t highlight this section, so we hope to learn more about their structure and use in our excavations over the coming weeks.

If you missed our recent webinar then why not catch up on the fourth instalment here:

At 06:05 a.m. on the morning of 7 June 1837, a sound like “the blowing up of an immense powder magazine” tore across the Hull quayside. But it did not come from the military fortifications of the Citadel, on the east bank of the River Hull, but from Humber Dock Basin. The boiler of the Union steam packet, about to embark for her home port of Gainsborough, had exploded. It was one of Hull’s worst peace-time disasters, yet has slipped from public memory.

Steam packets had been running from Hull up the East Coast from the 1800s and on the Humber since 1814. They were still a developing technology. The Union herself was only eighteen months old, and had previously carried cattle between Grimsby and Gainsborough.

The quayside was bustling with people preparing to board or to see off friends and family. The Union was moored near the eastern pier, close to Dock Basin stairs, with her bow towards the Minerva Tavern, stern towards the Basin entrance. Alongside her was the Don, the steam packet for Thorne. Passengers wanting to board the Don had to cross the Union’s crowded deck at midships. Other steamers in port included the Adelaide (Hull-Selby) and the Albatross (Selby-Goole-Hull-Yarmouth).

Thomas Jackson, a Methodist minister who had just been appointed to Doncaster from Yarmouth, had arrived with his wife and six children on the Albatross at about 5 a.m.. As they crossed the Union’s deck, Rebecca Ferrier, a poor woman in her 50s, who sold packets of gingerbread and nuts from a basket, tried to persuade him to buy, but he declined. He got the family on board the Don to continue their journey to their new home.

According to the Yorkshire Gazette, “in an instant the air was filled with fragments of the boiler, chimney, planks, bales of goods and human bodies”. When the clouds of steam and smoke dispersed, it was a scene of carnage. As Rev. Jackson later wrote: “Numbers of human beings were struggling in the water […]; others were stretched, mangled and bleeding corpses; some were shrieking in agony, having received wounds and scalds of a most dreadful nature.”

People, their luggage and bales of goods were blown off the vessel and high into the air. In Jackson’s account:

The sides of the steamer were blown out – the deck rent to shivers – the chimney was blown to an immense height, spinning round in its descent – the top of the boiler, in an almost entire state, was deposited in the open space in front of Minerva Terrace, fifteen or twenty yards from the vessel – other portions of it were driven in different directions, to a distance of from fifty to one hundred yards. […] The safety-valve was carried as far as Wellington-street, a distance of about eighty yards; where it struck and severely damaged the booking-office of the York steam packet Company. The weight […] attached to the safety-valve, was found in Humber-street, where it had alighted on the steps of Mr Veltman’s house, several of which were broken. (Jackson 1838: 10)

The Union’s iron crane crashed on to the crowded deck of the Don, while what was left of the Union herself sank.

And what of the human cost? At first, it was feared there were sixty to seventy dead, but the numbers came down as people thought to have been caught up in the explosion were traced.

Rev. Jackson found several packets of Mrs Ferrier’s gingerbread scattered at his feet on the deck of the Don. She had been blown from the Union over the Don – her cap, with part of her head, left on its masthead – and into the dock. Joseph Matthews, crane foreman and toll collector, had been blown 150 yards on to the rooftop of William Westerdale’s three-storey building. His body was shattered.

Police Inspector Cudworth found John Weston, a Macclesfield man, whose head was shattered and right leg almost blown off, dead, in a boat; and a young woman, Hannah Moody, lying on the gunwale with horrific head injuries, but “moving as it were mechanically”. She was sent to the Infirmary but declared dead on or soon after arrival.

The Union’s crane crushed Alice Dinsdale, a shopkeeper from Whitton, Lincolnshire, when it landed on the deck of the Don: “a frightful spectacle, her brain being exposed from a dreadful fracture of the head, and her body much mutilated”.

Other victims were pulled from the water. John Stephenson, from near Haxey, was found near the west pier, with severe wounds to the back of his head and his left arm almost torn off. Alfred Pape, a young commercial traveller for the grocers Wharton & Hustwick, 14 Junction Street, was found between the Union and the pier, with his legs jammed under a raft: he appeared to have drowned. Luke Green, from near Epworth, had been in Hull for a Methodist gathering and to view property. He was found between the Union and the east pier, his skull was shattered. His body was recognised by a fellow-member of the Oddfellows Friendly Society, who arranged his funeral.

Hull brewer Robert Chatterton and Richmond Tomlinson, landlord of the General Elliott, 88 High Street, had boarded the Union with one of her owners, packet agent and innkeeper, William Lewis, of the Steam Packet tavern, 2 Wellington Street. Mr Lewis was scalded in the face but survived. His friends were less fortunate. Mr Chatterton – who left a wife and nine children –was blown thirty or forty yards across the jetty, against the yard-arm of the Albatross, landing on gratings on her deck. His face was crushed and disfigured. Mr Tomlinson was found in the water near the new Corporation jetty, scalded, his clothes tattered. A middle-aged bricklayer, John Lowther, was picked up dead, his face and head covered in blood and his arms and body swollen.

Rebecca Clegg, the wife of a Salford hosier, well-dressed and wearing a gold watch, was found drowned in the Union’s cabin when the tide allowed access to the wreck. Her husband had been on deck and survived. They had been visiting friends in Hull and were on their way home.

The youngest victim was the fourteen-year-old engine boy, William Bland, who had part of his head blown away. The eldest was Thomas Jaques, a local furniture maker and dealer in his early sixties: he had been carried back to his nearby home on Junction Street, either already dead or dying.

The bodies were taken to the police station in Blanket Row. Hull builder John Hutchinson lost two sons – only learning, too late, that Arthur, “shockingly mutilated”, had been taken to the infirmary and died before he could visit, and then that William was lying in the Station House for identification, having been taken out of the dock scalded and drowned.

Fireman James Goddard, aged sixteen, died of his injuries in the Infirmary the following morning. Jane Woodhouse, a twenty-one-year-old from Thorne, had been on the deck of the Don when the chain of the Union’s crane fell across her, breaking her back. She died on 16 June.

Sarah Young, the stewardess’s 17-year-old assistant, had been among the missing. She was found on 20 June, floating near the West Pier, her face scalded and brains washed out. The story, however, was slipping down the national news as King William IV died the same day, and was succeeded by his teenaged niece as Queen Victoria.

Some two weeks after the explosion, Joseph Ireland, fireman, died in the Infirmary, having suffered severe scalds and a broken thigh. Similar injuries also killed John Wilkinson, rope-maker and landlord of the Crown and Anchor at Stonegravels, near Chesterfield, who had previously been thought to be improving.

An unidentified woman was washed up at Sunk Island on 30 June and buried the same day. It was thought she might have been a foreign broom-girl or nut-seller. The stewardess, Mrs Mary Anne or Anne Sampson, severely scalded on the body, had her wounds tended at the Steam Packet inn. She survived until 3/4 July, and was taken back to Gainsborough for burial.

The inquests, under coroner John Thorney, which began on the evening of the accident, led to the engineer, Joseph Gamble, being charged with manslaughter through negligence. He was brought from Hull Jail and charged at York Assizes on 11 July 1837, but was acquitted when tried in York on 20 July.

In total, there were twenty-three known fatalities, twenty-two of whom were identified. Eight may be buried in Castle Street. Rebecca Clegg’s inscribed headstone survives, but it is likely that Rebecca Ferrier, James Goddard, Luke Green, John Weston, John Wilkinson, Jane Woodhouse and Sarah Young may also be there. Mrs Ferrier and Messrs Green and Weston were all buried on 11 June, with about 12,000 spectators. 440 members of the Oddfellows turned out for their brother Luke Green. Richmond Tomlinson was buried the same day in Holy Trinity Churchyard.

Last week, we celebrated Yorkshire Day in Trinity Square, as part of the Council for British Archaeology’s 2021 Festival of Archaeology. In good company with the Minster, Petruaria Revisited and Roman Roads Research Association, our team of specialists welcomed the public to our marquee to share some of the finds and research coming from excavations at Trinity Burial Ground.

Alongside Louise, my role was to prepare and co-ordinate the event on the ground and we spent the lead up collating craft activities, selecting and boxing finds for display and getting a masterclass in the bones of the hand.

As would be expected, our excavations have furthered our understanding of Hull as a trading town, as demonstrated through the Russian bale seal that was one of our ‘Call Our Bluff’ items. Many of our visitors recognised this lead seal (which functioned very much like a wax seal on a letter but for trade goods) and were instead flummoxed by our unusual buttons which were not so recognisable without their fabric covers. The wig curler we thought was our best bluff was most people’s first guess, but the apple scoop kept everyone guessing. The finds also revealed the wonderful sense of humour of the people of Hull, from cheeky pipe tampers and figurines to clay pipe bowls sculpted into comedy portraits. This good nature continues today, as our visitors braved the rain and kept us smiling.

COVID restrictions meant that we couldn’t complete the bones of the hand craft activity on site, but our osteologists had a great time teaching visitors the difference between their carpals and metacarpals and sending them away with packs to complete at home.

Members of the public also contributed to our My-seum, with pictures and stories of items they would put in their own museum. We had ammonites, dolls, crabs and typewriters all added to the My-seum which will be printed onto banners and hung on the hoarding along the A63 as road works continue. For more information and to contribute your own item, please view our School hoarding challenge document.

Any families looking for activities to do at home over the school holidays should also check out Hull Museums’ Magical Museums summer activity booklet which includes some activities inspired by our work at Trinity Burial Ground.

For everyone involved, it was a delight to be able to share our excavation with the people of Hull. Louise and I would like to thank the team for lending us their expertise during the planning and their time on the weekend and all our visitors for making it worthwhile.

If you missed our recent webinar then why not catch up on the second instalment here:

If you missed our recent webinar then why not catch up on the second instalment here:

If you missed our recent webinar then why not catch up on the first instalment here:

Interested in archaeology? We’ll be taking people behind the scenes at the labs and talking you through some of their latest archaeological finds on Wednesday 14 July.

The webinar will start at 5pm.

To attend the webinar please click on the link below, a few minutes before it is due to start. Visit this webpage for more information about how to join Zoom webinars as an attendee.

All attendees will be on mute but there is the option to post questions in the live question and answer session. This can be found on the right-hand side of the page.

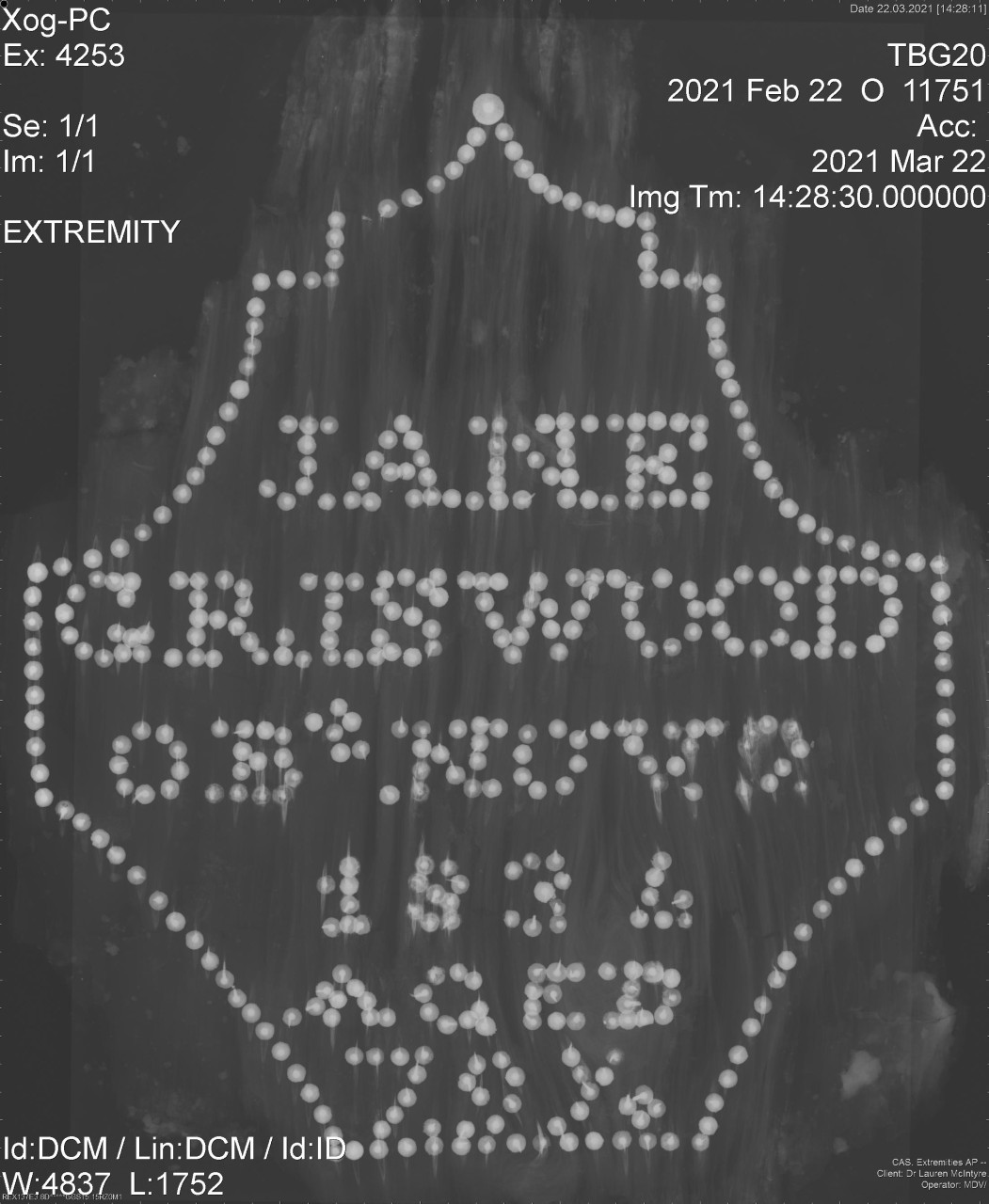

In our last insight, we learned about the life of Jane Griswood who was commemorated with a studded coffin plate, found during our excavations at Trinity Burial Ground. This week, local historian, Dr Marianne M. Gilchrist, returns to open the archives to the stories of Jane’s children.

Jane was already pregnant when she married Matthew Griswood in May 1774. Their first child, Hannah, was baptised on 27th November. Other children followed: John (b. Jan 1777), Jane (b. Jan 1780), Elizabeth (b. March 1783), Ruth (who died in Jul 1786, aged twenty weeks), a second Ruth (b. July 1787), Matthew (b. December 1789), James (b. October 1791), and Mary (b. March 1794), all christened at Holme-on-Spalding-Moor. Their youngest child, Martha, was born after they moved to Sculcoates in 1796 but died shortly afterwards.

The eldest, Hannah, married Thomas Cartwright, a brewer, at Holy Trinity in Hull on 28th May 1796 – just two weeks after her youngest sister’s baptism. They lived in Patrington/Keyingham area for some years, where they had several children, including twins who died just days after birth in May 1806. They seem to have moved back to Hull, but Hannah died young.

John Griswood’s profession was given as “mariner” when he married Ann Powdger or Poudger there on 18 September 1803. Later, he became a marble sawyer, and by 1808 was living in Bootham, York.

Jane junior – perhaps in service – married at St Mary’s, Beverley, on 23rd May 1809. Her husband was an Oxfordshire-born soldier, Corporal Thomas Bowden of the 15th Foot. He was 5’ 6½”, with dark brown hair, grey eyes and dark complexion. He was discharged from the army in 1816 as “old and worn out” at forty-three. In November 1825, he applied successfully for a pension of 6 d. a day as an out-pensioner of the Chelsea Hospital: again, he was described as “worn out”. After his death, Jane married a brazier (brass worker), James Robinson, on 8th October 1832, at Holy Trinity, Hull (her sister Ruth and her husband were witnesses.) They lived at Garden Court, which seems to have been off Posterngate. She was widowed again in October 1847, however, as her second husband was some fifteen years her senior.

Ruth had a short-lived child out of wedlock: John, buried at Holy Trinity on 22nd March 1809, when she was 22. She did not marry until she was 30. Her husband, Henry Starkey, was a 57-year-old widower. They married at Sculcoates on 19th January 1818. His first wife, Ann, had died the previous year.

Mary Griswood married a sailor called Hans Axellson, Axells or Saxton (probably Axelssen) at Holy Trinity on 5th September 1816. One of her children, born on 10th October 1827, was named Matthew Griswood Axellson, after her father. She also had a daughter, Mary, who was in service. They lived in Ropery Street, at one point running a lodging house. According to the 1851 Census, Hans was from Gammelby in Denmark: there are several places of that name, including one in Schleswig-Holstein, which is now in Germany. He died in November 1854. Mary died at St James Street, and was buried on 8 October 1868.

The marriage entries for all Jane Griswood’s children suggest they were illiterate. The brass studs picking out her name on her coffin may suggest the handiwork of her son-in-law James Robinson, the brazier. It was an old-fashioned style of commemoration – in keeping with Jane’s own age, and perhaps with James Robinson’s tastes, as he was only ten years younger than his mother-in-law.

Jane’s widower, Matthew, died in 1837, aged 85, and was buried on 24 April.

Ruth had been widowed a few months before her mother died. In 1838, she married again: her second husband was another widower, an agricultural labourer named Thomas Story. They lived it what was then called ‘Somerstown’, one of the new residential areas growing up to the east of the River Hull, along Holderness Road, and joining up what had been small, separate settlements. The 1841 Census shows their address to have been in Marfleet Lane. She died in March 1853, aged 55, and was buried on 19 March in the parish of St Andrew, Drypool.

John had returned to Hull by this time. The 1851 Census shows him as a widowed pauper, living with his daughter Mary, her confectioner husband John Storrer, and their children at 5 Duncan’s Place, off Manor Street.

Matthew junior, a bachelor, was a master mariner. His name surfaces in a dispute (reported in the press) over the validity of his vote in the 1838 election because he had been in receipt of Poor Relief, and thus not entitled to vote as Freeman. The Griswoods do not appear in the 1835 List of Electors, so this may have been recent. By 1861, he was living at the Kingston Alms House on Beverley Road (probably a euphemism for the Sculcoates Workhouse).

The tales of the Griswood family are likely typical for the nineteenth century and covers so many of the key issues of this period in Hull, including migration from the countryside, the impact of the Napoleonic Wars and connections with the European mainland as an international port.

Jane Griswood’s name is picked out in studs on the lid of her coffin, identifying her still after almost 200 years. Her story is typical of the country people who moved into towns and cities at the end of the eighteenth century. By then she was already a middle-aged woman.

Jane Akit was born at Bellasize (a small township about 4 miles east of Howden), in Eastrington parish, in spring 1755 and baptised on the 4th May. She was a daughter of William Akit and his wife Dorothy Agar. By the time she was in her late teens, the family lived at Holme-on-Spalding-Moor. There, she took up with a young man called Matthew Griswood, three years her senior.

By the time they married on 15th May 1774, Jane was already pregnant. This was not uncommon, especially in the countryside. Their first child, Hannah, was baptised on 27th November. Eight more children followed, all christened at Holme-on-Spalding-Moor.

The Griswoods probably moved to Hull in about 1795. Matthew found work as a gardener: it is unclear if this was already his profession, or if he had previously been an agricultural labourer. They initially lived in Sculcoates Parish.

Jane was already over forty when she gave birth to her youngest child in April or May 1796, baptised on 14th May. There is a scribal error in the Sculcoates Parish Register: the name has been written initially as “Matthew S. of Matt. and Jane Griswood, Gardener.”; then the “S.” has been corrected to “D.” but the name left unchanged – a slip of the pen repeating her father’s name. The baby was actually named Martha: she appears under her own name in the Sculcoates Burial Register for 19th October that same year, having died at the age of 6 months. The older Griswood children were already adults.

What is interesting, in looking at the marriage entries for all the Griswood children, is that they were illiterate – they make their mark rather than write their names. Next week, we’ll learn more about their lives and see if the historical records can shed any light on who may have commemorated Jane’s life in such an unusual, and old-fashioned, manner for the time.

This research was undertaken by Dr Marianne M. Gilchrist, a freelance historian, who grew up in Hull and studied at St Andrews. She has worked at the University of Glasgow and the University of Hull and has written and published on various subjects of art, history, literature and architecture. Recently, has been researching the monuments at Hull Minster.

At the last webinar we didn’t get chance to answer all the questions that were submitted. We said we’d answer them for you, so we’ve gathered them all together and published them below.

If you enjoyed the webinar then we’ve got great news, we’ve organised a second one for Wednesday 14 July at 5pm. We’ll be publishing further details about how you can attend this in the next few weeks so make sure you subscribe to get all the latest information.

Have you found any items of gold and silver?

Yes, we have. Many of our archaeologists had not found any items of precious metal before working on this site as it’s usually a rare occurrence. We’ve found gold and silver jewellery, including hallmarked wedding bands. We found a gold guinea, issued in 1804 during the reign of George III. It was found in loose soil and not associated with a burial. A more unusual find was a top set of dentures made of gold, a stable metal which would not tarnish in the mouth. The teeth used in the dentures look to be real human teeth, which was common practice in the early nineteenth century.

You noted that the headstones were recorded by the local society in 1980 some 120 years after the last burial and since then a lot have become illegible. Does this mean the erosion of headstones has increased in recent years due to environmental factors?

Yes, unfortunately many of the headstones had weathered and become illegible in the past forty years.

Have there been any ghostly goings on or incidents?

No, thankfully not. Any ghosts are evidently observing the social distancing measures in place!

What was the average age of death and can you tell what the main cause of death was?

At the moment, it’s too early to say while we’re still excavating and examining burials, but these are the sorts of questions we’re looking to answer as we do further analysis. The burial ground was in use for nearly eighty years so we expect that there will be a lot of variation in terms of age and cause of death over this time, and in different sections of the population.

What was the criteria for determining how many of the 'residents' you could fully examine? How was the 1500 number reached?

All burials are being surveyed, photographed and recorded in terms of position, orientation, grave goods, burial dress and fastenings. Skeletons are being assessed for completeness, condition, potential for aging, sexing and the presence of the skull and complete long bones for further examination. Unfortunately, many burials don’t meet the standards required for full osteological analysis. A sample of 1500 skeletons (approximately 16% of the total) are being examined on-site before reburial. It is standard to sample very large cemetery assemblages and this number was reached in agreement with the Church. The sample size should be sufficiently large to be statistically valid and explore demographic changes over time and spatial variation within the cemetery.

How do you distinguish between a burial item as evidence of migration, or evidence of trade?

It’s not really possible to say with certainty how any individual item manufactured abroad came to the town and into someone’s possession by looking at the object alone. You need some context to make an informed interpretation. If the items are found with an identified individual and if any records can be found about their life history, or if biochemical analysis (e.g. ancient DNA, stable isotope) reveals something about their likely origins, you could surmise how they and their possessions came to be there.

Will all the findings be published for the public to read?

After finishing the excavation, we will produce an initial assessment of our findings. We will then undertake further specialist analysis which will take several years. We expect to publish our results as a large book and probably also as a booklet, which will be submitted to the Humber Historic Environment Record and the Hull History Centre. For those interested in lots of specific details, specialist reports on the findings will be submitted to the Humber Historic Environment Record and will also be made publicly accessible via Oxford Archaeology’s online library.

Are the burial registers available to see online?

The Holy Trinity Parish burial registers record the interment of some 44,041 individuals between 1783 and 1861. The registers have been scanned, transcribed and added to a digital searchable database. We still need to check and cross-reference some of this data with other records at Hull History Centre now that it has reopened in the wake of the pandemic, but we plan to make this a publicly accessible resource later in the project.

Are visitors allowed to see any of the site or work?

We've had strict COVID-19 mitigation measures in place on site to ensure the safety of our staff. We’ve been reviewing our safety precautions at regular intervals and, if we’re able to host visits from members of the public before the excavation finishes, we will advertise any opportunities here on the Highways England archaeology webpages.

Were any religious rituals carried out in the process of re-burying?

We have been liaising closely with Hull Minster throughout the project. The Priest in Charge gave a blessing ahead of the start of works, and we’re looking to have a memorial event once COVID-19 mitigation procedures have eased.

If you missed our recent webinar, catch up on the third instalment here:

If you missed our recent webinar, catch up on the second instalment here:

If you missed our recent webinar then why not catch up on the first instalment here:

Mark Gibson talks about what it’s like to work as an Osteologist on the excavation of the Trinity Burial Ground in Hull.

Far from home

The Trinity Burial Ground excavation from an archaeological viewpoint is of great interest. It will be one of the largest post medieval cemeteries that has been excavated in the North of England. The data we generate from this project will help contribute to our understanding of the lives of people in 19th century Hull, but also be used to compare with data from other populations in the UK from the time. This exciting prospect has resulted in a horde of archaeologists from across the UK and beyond coming together to work on this special site. Working away from home for such a prolonged period of time and especially during a pandemic does however bring its own challenges, and the mental health of the team is a top priority for both Oxford Archaeology-Humber Field Archaeology and Balfour Beatty.

Imagine spending months away from home, working long hours, and being unable to see your friends and family in a city you barely know. This is the reality for many archaeologists across the country, not just here in Hull. Loneliness, homesickness, stress on personal relationships caused by being apart, depression and anxiety have all been present in the lives of the archaeologists during this project, but we are doing all we can to provide a safe and comfortable workspace and home away from home.

To help support staff, both Oxford Archaeology-Humber Field Archaeology and Balfour Beatty have provided trained mental health first aiders on site to talk to at any time. These mental health first aiders provide regular “drop in” sessions for people to attend, and we’ve had a few special mental health sessions for the entire team that have proved very useful. I myself have spoken to the mental health first aiders a few times while I’ve been on site and can attest to the professionalism of each and every one. Outside work hours, we have access to a counselling helpline that is available for all staff and their family members 24/7, 365 days a year.

By far the biggest thing that has helped keep on top of people’s mental health is the simple act of being there for each other. Working and living with the same people for months on end can cause friction, however it can also forge the strongest bonds of friendship. I have been amazed by how well people have come together and supported each other on site and off. Though the shadow of Covid-19 has loomed over us all for the duration of this project it hasn’t stopped us from coming together and supporting each other. A series of online quizzes hosted by the more proactive and technologically capable members of the team proved very popular and enjoyable. Sitting outside at tea breaks with a coffee and chatting together (at a safe distance), or simply listening on site when someone needs that have all contributed to maintaining the mental health of the team, and at the end of the project I personally know I will walk away with a host of amazing new friends and colleagues.

Conclusion

I hope this gives some insight into the challenges we face daily here on the A63 project and how by working together we have managed to overcome them. Naturally there are always new challenges each day, and not everyone is instantly resolvable, but we’ve got a great team out here and I’m proud of the way we have approached this project and with perseverance will see it through to completion and be able to tell you all the story of this incredible site.

Dan

Friday 30 April - Overcoming challenges part 1

Hi all, my name is Dan and I’m one of the fieldwork supervisors working on the Trinity Burial Ground site. I’ve been working in commercial archaeology for about six years now, I was one of the archaeologists who worked on site in 2015 when the trial trenches were being excavated and it’s a great pleasure to be welcomed back to the main excavation work and see the site through to its completion.

While the other weekly insights have had you meet the team and showcase some of the amazing archaeology we are discovering, as well as giving behind the scenes looks at the post excavation analysis going on; I’m going to talk about some of the challenges we have faced over our time on site and how we have overcome them.

Archaeology -1 part digging three parts water management

One of the biggest challenges we have had on site was the issue of water. As our excavations proceeded deeper and deeper it became very apparent that our working conditions would soon become very much soggier. Given the delicate nature of excavating human remains, one of the last things we want is for site to be underwater, and for the already hard clay to become a slippery sticky nightmare. Small bones can become lost very easily in layers of clay, and the ground became hazardous to walk upon due to the risk of slipping.

Thankfully, archaeologists are resilient and resourceful, and with the help of our principal contractor (Balfour Beatty), we were able to manage the water and the risks it posed so that works could resume safely.

One of the first measures taken was to lay down eco grid (gridded plastic squares that can be clipped together) to provide firm walkways for people to walk on. This stopped people from walking on treacherous ground, it also served to control where people could and could not walk, so that the archaeology was protected from being trampled on and lost. When the eco grid became too clogged up with dirt to be useful, they were jet washed clean and fresh walkways constructed.

To deal with the water itself Balfour Beatty provided us with pumps and a team of workers to go round and pump away the worst of the water.

Simultaneously a few brave archaeologists, who didn’t mind jumping in and bearing the brunt of the wet and the mud, worked furiously to clear areas of site so that large sumps could be dug. These sumps helped drain water from higher areas of site and served as useful areas to channel water from other areas of site into to then be pumped off site.

Fortunately, with the weather improving and the ground now drying up again we can look forward to much drier conditions and archaeologists.

Getting heard

Communication is key they say and that is never more true than on large infrastructure projects like this where we have where we have scores of archaeologists, split into many teams. Simple miscommunications can lead to huge errors in our work that take time to fix, or if it relates to a health and safety matter endanger ourselves and others.

In order to minimise these risks Oxford Archaeology-Humber Field Archaeology and Balfour Beatty have several methods of getting information around site. The easiest way we communicate messages to staff is through morning briefings. These briefings let our teams know where they are working, who with and what other teams are up to and other important project wide messages.

Some messages cannot wait until morning to be addressed and for this, we use internal emails and a messaging group to keep everyone informed. The messaging group has the bonus of being a convenient place to group chat after hours, though strictly moderated and in line with company policy on dignity and respect in the workplace.

Balfour Beatty hold monthly meetings called “Voice meetings” and these are a chance for members of staff from all contractors on the project to get together and raise issues in a non-judgemental space that get passed on to management to deal with. No management attend the meeting, and none of the issues are attributed to individuals. At each meeting feedback from points raised in the previous meeting is given.

Through all these mechanisms we somehow manage to keep everyone well informed….that said I’m still waiting for someone to order new buckets in.

To be continued.

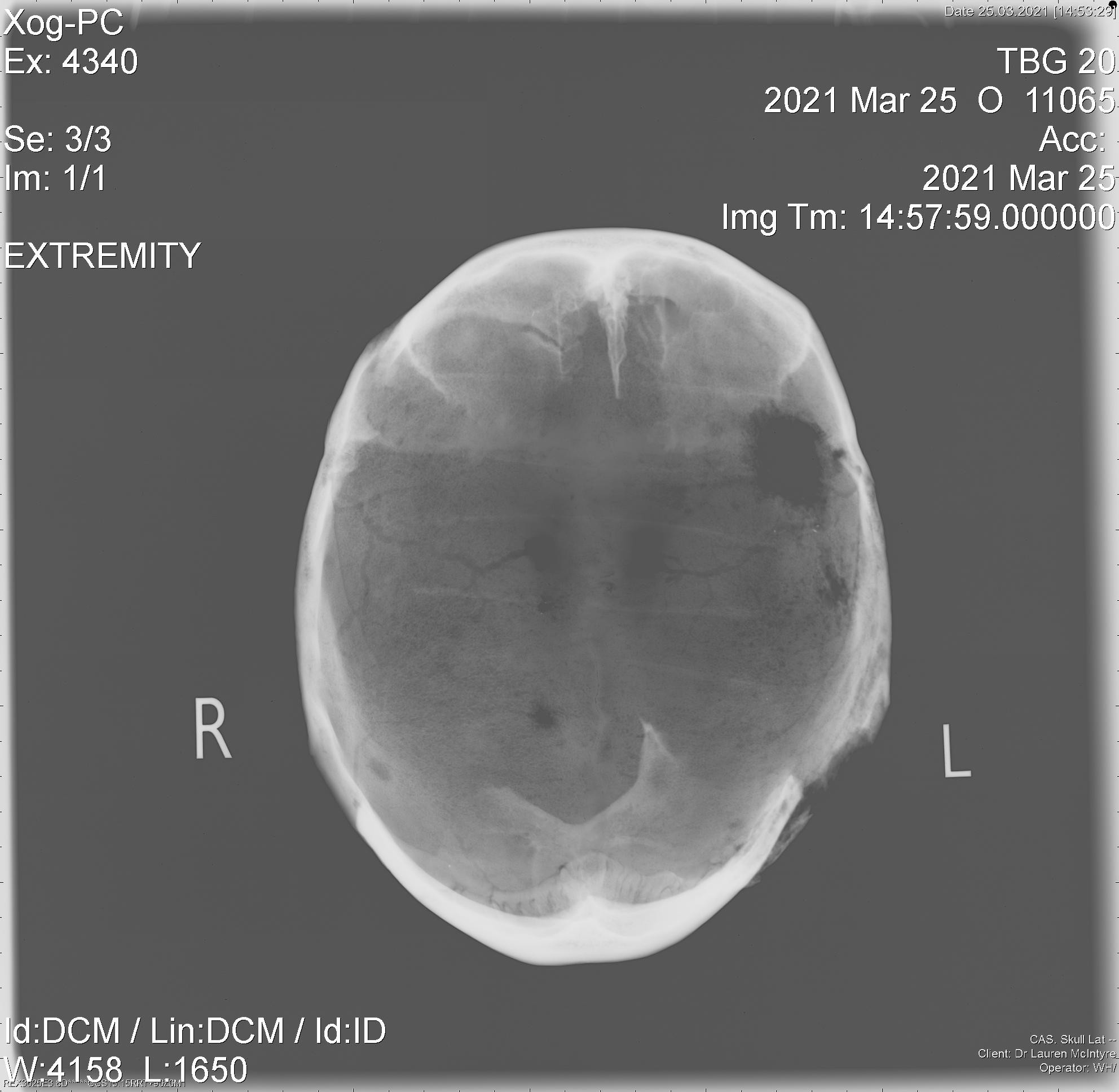

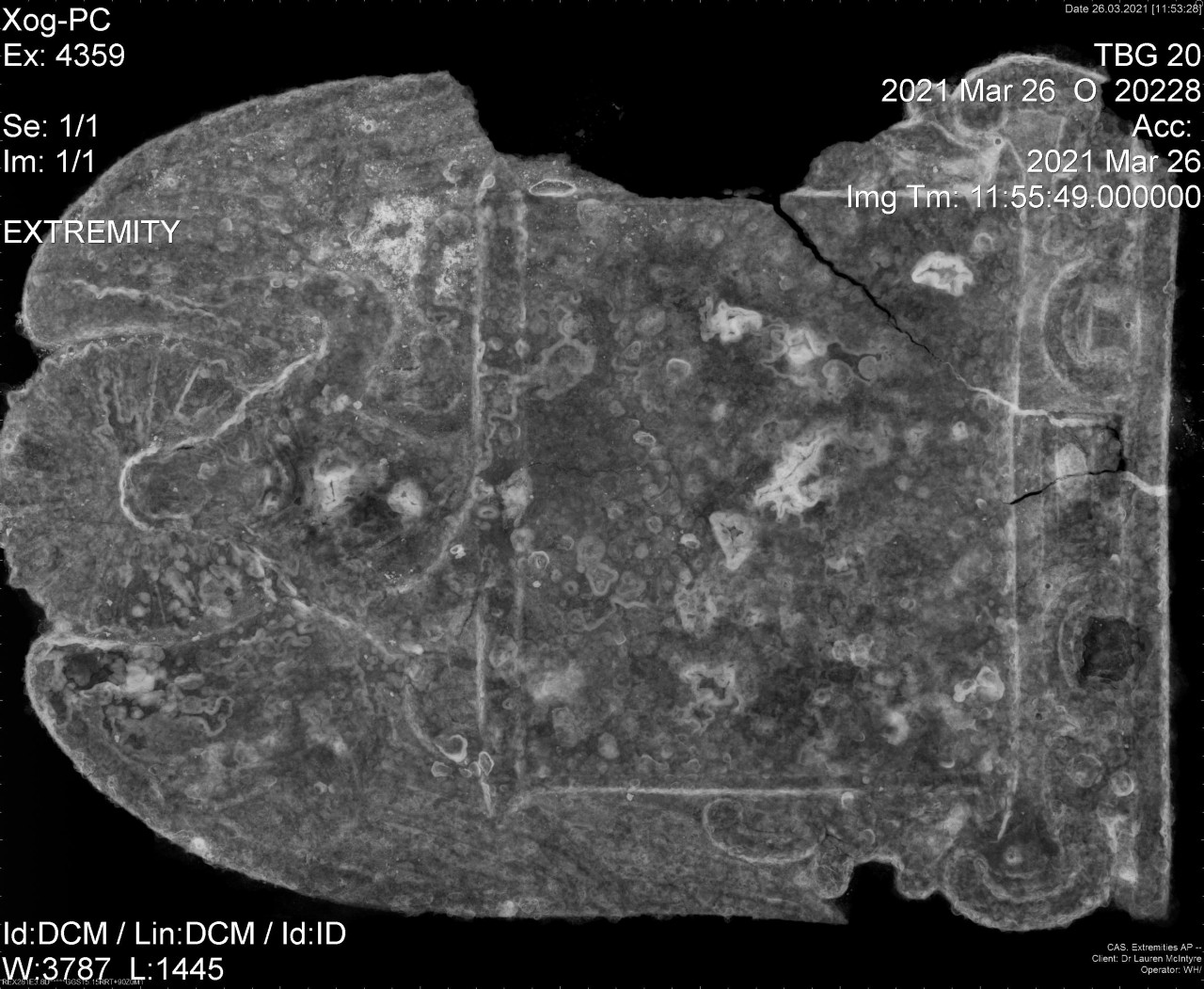

Friday 24 April - Radiography

Part of the skeletal analysis being undertaken at Hull Trinity Burial ground involves x-raying bones. Oxford Archaeology-Humber Field Archaeology are working in partnership with Reveal Imaging, a mobile radiography unit.

A radiography machine is brought to site to take digital x-rays of bones. The x-rays help us to diagnose trauma and diseases which cannot be identified just by looking at the bones in the lab.

So far, we have x-rayed bones from almost a hundred skeletons. If a skeleton has a broken bone, we can look at the x-ray immediately and see both how the bone broke, and how it has healed.

For example, in the next picture, we can see the left thigh bone has broken in a spiral pattern. The break has a line that encircles the bone shaft like the stripes on a barber pole or candy cane. In modern times this type of break is a very serious injury, usually caused by a car accident or high impact sports accident such as skiing or snowboarding.

The person from Trinity Burial Ground might have sustained this injury falling off a horse or having an accident on a ship.

We can also use the x-rays to diagnose other diseases such as cancer.

The next image shows an x-ray of a skull. The black speckled areas are lesions found in a type of bone marrow cancer called multiple myeloma. Not all these lesions were visible when we looked at the skull in the laboratory. In the 19th century there was no cure for this disease. Now it is treatable with chemotherapy and steroids.

We have also x-rayed some of the coffin fittings found at the site. This helps us to see the shape and designs more clearly where they are corroded, as in the following images. This information can be used to date the coffin, as different designs were used at different times.

The breast plate above shows an angel design which dates to between 1820 and 1858. As far as we know, it is the first example of this breast plate design found archaeologically in the UK.

Hello, I’m Sam McCormick and I’m one of the archaeologists who has been working in the tent on Castle Street to excavate the burials. Late one afternoon last week, I discovered this amazing coin purse. I found it in place by the right hip and leg of someone we initially think was an elderly male. The purse contained nine coins (eight large and one small) and were quite weighty so they could potentially be of good value. The bone toggle and a mother of pearl button were all that remained of the purse itself, which would have been made of leather that hasn’t survived in the ground. It’s just one of the many personal effects we’ve found with the burials on this site, along with things like buttons, hair combs and cufflinks.

This excavation at Trinity Burial Ground is brilliant as it’s the first major analysis of a post medieval society in the north of England. I also love the late 18th to 19th cemetery cemeteries. It was the age of industrial advances and medical science so the pathology on the people buried here is extremely fascinating! I first got into archaeology when I was three or four after my mum put me in front of the telly to keep me occupied. A show called ‘Meet the Ancestors’ was on and I was so enthralled I began to take my mum’s make up and mirrors and bury them in the garden, and then pretend I’d made a discovery. She regrets putting me in front of the telly since. And it just snowballed from then to where I am now.

Here Ashleigh talks about the different coffin fittings we found while working at Trinity Burial Ground.

Stephen Rowland is a Project Manager at Oxford Archaeology, overseeing the archaeological work for OA with Humber Field Archaeology.

Steve has a long-held fascination with funerary archaeology and human osteology and has previously managed archaeological investigations within the crowded post-medieval and industrial-period cemeteries at Coronation Street, South Shields (Tyne and Wear), Redearth, Darwen (Lancashire), and Swinton (Greater Manchester).

He’s been involved with the A63 scheme since 2014. And recently attended an online meeting of a group of volunteers working with Hull Minster. They are currently researching the history of the Minster’s main burial ground and the market at Trinity Square from home, with the aim of sharing the history, stories and rich history of the Minster and its surrounding area in a new visitor and heritage centre ready for when it can open to the public.

The volunteers had a lot of questions for Steve and here we share some of his answers with you.

How does this burial ground reflect the changing social structure of the town?

We think that the wealthiest people occupied plots in the more accessible parts of the burial ground. Their high-quality coffins, well-spaced graves, tombs, and elaborate monuments are generally found along paths emanating from an entrance on Castle Street within the eastern part of the area under investigation.

Within the western and far eastern parts of where we’re working, the situation is more varied. There are occasional good quality fittings, but the burials are denser, suggesting that these are less wealthy people. Nonetheless, many have been able to afford family plots and erect grave monuments.

Charting change within the burial ground is not that easy: it was in use for a relatively short time (less than 80 years), and the graves rarely produce chronologically distinct artefacts.

What are the most exciting things you’ve found?

We recently uncovered a mortsafe, which is an iron cage either built into or around a coffin and designed to prevent body snatching. We know from historical records that bodysnatching was happening at the time the cemetery was open, but this is our first clear evidence of preventative measures.

(Mortsafe)

Tying in with that was a grave that contained the remains of at least one person who had been anatomised (dissected for medical study). We’ve had numerous burials with evidence for autopsy (for example, removal of the top of the skull), but this individual looks to have been extensively examined, with various body parts displaced and often sawn through.

We had a well-preserved coffin inscription, with the name, age and date of death of the buried individual picked out on the surface of the coffin lid in copper studs. The use of the Latin term ‘obit’ rather than the far more common ‘died’ suggests that the family, and perhaps the elderly lady herself, were classically educated.

(Coffin inscription)

It has also been nice to find several plate burials. It is thought that the plates originally held salt used to ward off evil and the devil in particular.

And what are the most common things you’ve found?

We’ve had a wide range of coffin fixtures and fittings, with occasional coffin plates as well as metallic lace trimmings and studs that were used to secure fabric coverings.

We’ve found a lot of clothes fastenings like buttons, and a reasonable amount of personal adornments and jewellery, which people were buried in.

A number of the burials have been found with coins over the eyes (to stop the disconcerting event of the eyelids popping open during viewings). Others have had coins that may have been in pockets, including several that are Dutch rather than British.

Is there anything you expected to find, but didn't?

We’ve had fewer lead coffins than expected – which is no bad thing.

We’ve found a lower density of burials than expected. We suspect that the poorest people were buried in the south of the burial ground, which is remaining untouched.

Have you been able to identify any particular people?

The East Yorkshire Family History Society recorded all the headstones in the 1980s, and we surveyed the site again prior to commencing the excavation. However, many of the grave plots have been reused multiple times, and the space between plots has been filled in with burials. This has made it very difficult to associate individual skeletons with the details recorded on nearby gravestones.

Moreover, whilst many of the burials have evidence of coffin plates that would have recorded their name, age and date of death, these details were generally painted onto very thin iron sheeting that has rarely survived intact. To date we have been able to identify only a handful of people from their coffin plates.

A notable exception was a burial covered with two iron plates. These coincided with the position of a headstone to William Watkinson, who died aged 32 years old in 1835 when a boiler fell on him. The plaque on the monument is thought to derive from the boiler, and it is possible that the iron plates encountered may be elements of the offending object.

Do you have any questions for Steve and the team?

If so, make sure to get in touch with us at A63CastleStreet.Hull@highwaysengland.co.uk and we’ll answer them here.

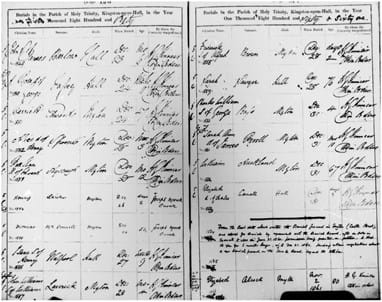

This weekend marks a historic moment as the latest census takes place on Sunday 21 March 2021. The census is a count of everyone in the country on a given day, and in the UK, it has been taken every 10 years since 1801 (except for 1941 due to the Second World War).

Trinity Burial Ground, belonging to the parish church of Holy Trinity (Hull Minster), was in use between 1783 and 1861. The 1841 census was the first to list the names of each individual, as well as their sex, occupation and age rounded down to the nearest five years, making it the earliest useful census for researchers matching up details recorded on monuments in the cemetery and in the burial register.

Burial records are often used to supplement the 19th century census returns to provide additional information for the family historian. In parish records, you may find the birth, marriage, and death of the person you are looking for but little else. With burial records you can be luckier. Trinity Burial Ground’s burial records offer the additional information of age at death, and the name of the informant declaring the death, usually a near relative. It’s with the opening of Hull General Cemetery in 1847 that burial records contribute much more information. As well as the name of the deceased and their age at death, the cemetery authority also recorded the last address of the deceased, the name of the informant, the cause of death, and who the minister was who attended the funeral. To the family historian, and to the social historian too, this is indeed a treasure trove to explore.

With the information provided, a researcher can identify and plot the spread of the cholera epidemic of 1849 that killed 3% of the town’s population. Using the addresses, the source of the epidemic can be identified, and its surge and ebb can be mapped out over the town. The social class of the victims can also be measured, as can the ages and the gender.

(Parish Register)

From a preliminary study made in 2018 more women and children died from it than men. It’s difficult to say with certainty why that occurred but it probably lay in the fact that the women and children were more in contact with the dirty, infected water than their male counterparts. This is just one example where other historical records supplement the information recorded on the census returns. Burial records, rather than an end to research for the family historian, can often be the beginning of a whole new chapter.

The East Yorkshire Family History Society (EYFHS) produced a book of the monumental inscriptions of the stones in Trinity Burial Ground Castle in 1985. Also included in the book are the parish register entries and a map showing the position of each stone at that time.

Another survey in 2015 showed that some of these stones have gone, making the society’s study an invaluable source of information that had otherwise been lost. The book is available from the EYFHS website shop page under Holy Trinity, Hull Castle Street Burial Ground.

(Gravestone)

(Monument recording)

Among the Hull residents who will be captured in this year’s census will be the archaeologists living and working in the city. It’s intriguing to think that future historians might wonder why so many archaeologists were in Hull in 2021 and might make the connection with the excavation at Trinity Burial Ground, which will be recorded for posterity in the Humber Historic Environment Record.

To find out more about the East Yorkshire Family History Society, visit our website at www.eyfhs.org.uk or get in touch by emailing helpdesk@eyfhs.org.uk

Census records from 1841 to 1911 are available online and can be searched by name or browsed by place. More information can be found on the The National Archives website.

Did you know?

The 1911 census was the first where the form filled out by the householders has been kept on file. Prior to that, dedicated ‘enumerators’ collected census data by doing door-to-door interviews or transcribing information provided by the householder to a separate ‘enumeration’ book. This led to spelling mistakes due to bad handwriting or the enumerator mishearing what had been said, especially when they weren’t familiar with the local dialect.

Census data shows that the population of Hull grew rapidly between 1801 and 1901, Hull’s population increasing almost tenfold from 27,609 to 239,517. This was in part due to a change in boundary changes as the town grew, but also resulting from increased migration from elsewhere in the country and from abroad.

As part of British Science week we take a look at how we’re using technology to analyse the burials at Trinity Burial Ground.

British Science Week starts today. Here we look at how we’re using different types of technology to carry out our work at Trinity Burial Ground, Hull.

In her video she talks about the work she does.

Hi, I’m Angela Fawcett and am currently employed as a Field Archaeologist with Humber Field Archaeology (HFA). They are a Hull based company, who work extensively within Hull and the East Riding and are working in collaboration with Oxford Archaeology North on the A63 project.

I live in Beverley, East Yorkshire, and have always had an interest in history and archaeology. An advert to join East Riding Archaeological Society (ERAS) in 2009 is what started me on my current path.

The society is a mix of enthusiastic amateurs and professionals with a commitment to promoting the archaeology of East Yorkshire and a very good place to start if you are interested in local archaeology. I turned up with very little knowledge and no experience and was welcomed and encouraged.

We hold regular and varied lectures on national and regional projects (currently online). Post-pandemic, we will continue with our monthly Field Studies programme – sorting and recording pottery from Romano British kilns from Holme on Spalding Moor.

Members also receive the Society’s major publication, ‘The East Riding Archaeologist’ and regular newsletters. ERAS also organises day trips, weekends away and social events. Members can get involved in geophysical surveys and, sometimes, excavations. Visit www.eras.org.uk or our Facebook page if you are interested in joining us. Go on – have a look. Who knows where it will take you?

This inspired me to begin a six-year period of part-time study at The University of Hull whilst working as the Administrative Officer in a local Nursery School, volunteering at excavations in school holidays and continuing as a busy Committee Member with ERAS.

In 2012, halfway through my studies, I became a Commercial Field Archaeologist. I consider myself really lucky to live and work in Hull and the East Riding doing something I adore. I’ve worked on some amazing sites of national significance on the Wolds and Holderness – for example Iron Age chariot burials and early Anglo Saxon Cemetery and settlement sites. I have also worked extensively in Hull Old Town – including the Humber Street regeneration, the dry dock and the C4di building.

More recently I have been involved in Highways England funded developments at The South Blockhouse Project and at Hull Minster. The South Blockhouse Project invited community involvement and it was wonderful to see how enthusiastic the Hull population were about their amazing heritage – with many visiting weekly to see how we had progressed.

After excavations at Hull Minster it was natural to want to be part of this project. Every regeneration project in Hull gives archaeologists an opportunity to explore previous generations. It’s an incredible opportunity to explore and understand the social and economic history of the population of Hull at a time when it was experiencing huge population expansion.

When restrictions are lifted I am looking forward to showing our visiting archaeologists the cultural sights and sounds of our lovely city.

Hi, my name's Nathan. I am one of the project supervisors, responsible for leading a team of archaeologists in the excavations out here at Trinity Burial Ground.

Here I talk about how I got involved in archaeology and what it’s like working on this project.

How did you become an archaeologist and why?

Having always had a passion for history I went to University of Chester to study history and archaeology, planning on becoming a teacher. However, I found that I much preferred being in the field getting dirty and handling history, than just simply reading about it in books.

When I completed my degree and having developed the itch to keep exploring the next archaeological horizon, I approached a unit that I had previously volunteered with and was fortunate enough to be given a paid post. And now four and a bit years later my career has brought me back home.

Have you worked on any other sites in and around Hull?

Unfortunately, no, this is my first time excavating within Hull, having spent most of my career in the south working on other large-scale projects such as HS2.

What's so interesting/exciting about this project?

As with any large-scale cemetery excavation it provides us with a snapshot of the population from the period and region concerned. Giving us useful information on the population, like where they came from, their diets, the diseases that afflicted them, possibly even how they died. With this data we can compare it to other cemeteries and see how the population differed across the country and even throughout time. This one just has the added bonus of being in the great city of Hull.

What does this project mean to you as someone local to Hull?

For one thing, those individuals we are excavating from the burial ground are likely to be distant relatives, which gives it a unique connection, unlikely found on other sites.

But also, I know how important these road improvements are to the region and it gives me a sense of pride to know that the work I am doing will have a positive impact on the lives of people I know.

Lauren is one of the archaeologists working on the A63 Castle St scheme. Here she talks about how she got into archaeology and the work we’re doing in Trinity Burial Ground, Hull.

About weekly insight

Each week, our archaeological team and guest contributors will shed light on themes, personalities, discoveries and personal experiences which tell the story of Hull.

We will be going behind the scenes on the archaeological work in the Castle Street area and finding out more about other recent digs and finds in and around the city.

We will dive into the archives to find out more about the transformation of Hull from a medieval market town to a commercial port at the centre of the Industrial Revolution to the celebrated modern city of culture we have today.

Behind these sweeping changes in the fabric of the city, we will also be homing in on individual human stories about the lives and livelihoods of people who have lived here through the ages, and exploring why their stories are important to Hullensians today.

These ‘Weekly Insights’ will be posted here every Friday, starting in February, and shared on our social media feeds. You can find us on Twitter and Facebook. If you would like to be updated on the latest news and information on the A63 archaeology, make sure to subscribe to our new email list.

We welcome your comments, feedback, and questions arising from the weekly insights. Please get in touch via email or social media.

Do you have any burning questions for our archaeological team?

Do you have any insights about Hull’s heritage which you would like to share?

Do you know of any historical mysteries that we could investigate further?

If you do, get in touch with us at: A63CastleStreet.Hull@highwaysengland.co.uk

Keep in touch with what we're doing

Sign up for email bulletins about our archaeological work around Castle Street - we'll let you know when we have new findings and when a new insight is posted.